It was a Friday morning. We were finishing a four-night venture to northern Vermont, our first foray after completing our 14-day quarantine in Vermont. The plan was to meet up with family for the weekend in central Vermont, so we had time to take a hike or ride our bikes before traveling south. Seeking a nearby destination to explore, I scanned our road map (yes, we carry paper maps), swiped through Google Maps, and opened up the AllTrails app (great for identifying walking trails) and the TrailLink app (for rail trails). On this trip, we were also carrying a book titled Erratic Wandering, An Explorer’s Hiking Guide to Astonishing Boulders in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont (authored by Jan & Christy Butler). My mom found this book in a local bookstore and bought me a copy knowing how much I like to explore in the woods (she also purchased a copy for herself, for the same reason).

The combination of these resources identified Sentinel Rock State Park, a relatively new Vermont state park, about 30 miles south of our Harvest Host overnight stay at Lavender Essentials of Vermont in Derby Line. In addition to the namesake Sentinel Rock, a large glacial erratic, a hiking trail in this park offered a chance to stretch our legs in a northern hardwood forest prior to the drive south. With no specific expectations pertaining to our destination, we set off along the winding and hilly country roads of northern Vermont towards the park.

When we arrived at Sentinel Rock State Park, a few uphill miles east of Willoughby Lake, a number of objectives were immediately met. First, we found a level, empty gravel parking area that afforded a panoramic 270-degree view to the south and west, and second, we had numerous bars on our phones so we could download the newspaper and catch up on recent events.

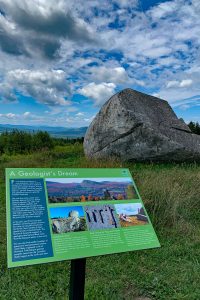

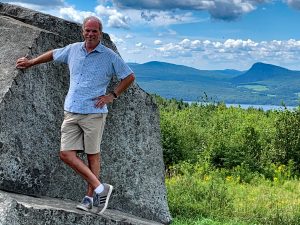

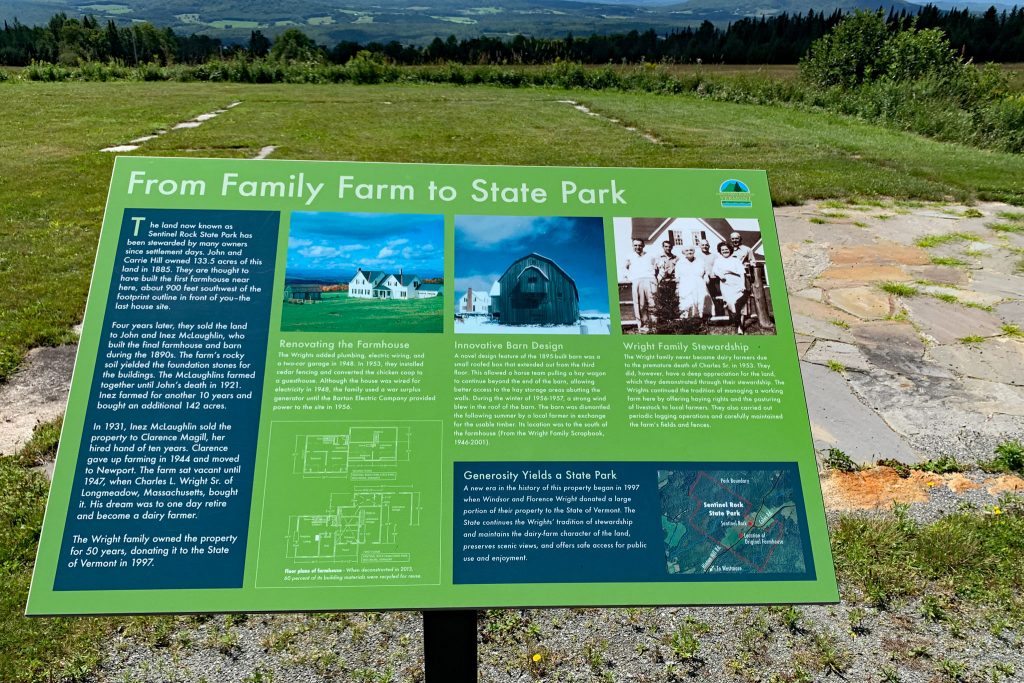

After scanning the newspaper and eating a snack, we walked toward the featured attraction in the park – Sentinel Rock. Signage installed by the Vermont Departments of Forests, Parks and Recreation described the history of the surrounding area and the Wright family farm that was present prior to establishment of the park. We learned the Wright family donated 356 acres to the State in 1977 with the objective that the land be maintained in good condition and shared with others who would appreciate the setting. The farm buildings were gone, but stone foundations remained, and we walked around the former building sites imagining how the buildings looked. We followed a newly established trail that clearly was designed to meander across the landscape and reached the rock. Of course, we had to climb on it and take a few photos.

Sentinel Rock

A glacial erratic is a rock transported and deposited by a glacier having physical characteristics different than the native rock upon which it is sitting. Glacial erratics can be all sizes, but the really big boulders are what we see and remember. The largest known glacial erratic may be Okotoks Erratic (also known as “Big Rock”), a quartzite boulder located in Alberta, Canada. This erratic is about 30 feet tall, 125 feet long, and 55 feet long (the size of a three-story apartment building), and it is now on my list of places to go. In contrast, Sentinel Rock is “only” about 10 feet tall and 10 feet wide.

The origin of these large boulders was a paradox for early scientists, who thought they were evidence of vast flooding. By the 19th century, geologists concluded erratics were evidence of an ice age and glaciation. Erratics of all sizes can occur through processes such as:

- abrasion and scouring, which occurs along the glacier’s bottom and sides;

- plucking, or cracking pieces of bedrock as the glacier moves by; and

- avalanching rock onto the top of the glacier, which can occur when the glacier undercuts a cliff or rock face.

It’s likely the largest glacial erratics we observe occur as a result of rock avalanching onto the top of the glacier and then being transported near the top of the glacier, limiting glacial abrasion and depositing the erratic at the top of the glacial deposits. In some cases, the glacial erratic may even have its original fracture planes, demonstrating limited breakdown of the rock by the glacier and/or perhaps a relatively short transportation distance.

After evaluating the composition of a glacial erratic, geologists can determine the source rock. Thus, the erratic can be used to determine the glacier’s path. According to signage at Sentinel Rock State Park, rocks and boulders in this park were carried by glaciers from as far away as Canada’s Northwest Territories. The signage also stated Sentinel Rock is a granitic rock that is likely from the “Newport Pluton”, which to be honest I’ve been unable to definitively locate on a bedrock geological map.

After our inspection of the erratic, we hiked about 1 ½ miles along the forest trails in the park. We observed a few flowering plants that we didn’t recognize and used the app PlantSnap to identify them – white meadowsweet and wall-lettuce. We typically try to “read” the forested landscape to figure out what formerly might have been a pasture, a woodlot, or a former logging trail. We had fun trying to decipher any clues this forest offered. Overall, it was a good hike – not muddy, not buggy, and not sticky.

White Meadowsweet

Wall-Lettuce

Back at the campervan, we ate lunch and enjoyed the view. Prior to this morning, neither of us had ever heard of Sentinel Rock and the newly established park. But, thanks to the many resources we carry, we found a great waypoint on our travels that combined history, hiking, geology, photography, and nature. It was time to leave, but first we needed to use those resources to find ice cream!

The former farm house location

A parking spot with a view

Lake Willoughby

View along the trail